Financial incentives in hospice

When you look at the numbers, hospice isn’t exactly thriving compared to other healthcare services. In 2021, hospices saw 13.3% in Medicare margins. Meanwhile, inpatient rehab saw 14%, SNFs were at 16.5%, and home health saw a nice 20.2%. What these numbers don’t show though, is that for-profit hospices have nearly four times the margins that nonprofits do (19.2% vs. 5.2%).

The disparity in margins between for-profit and nonprofits is too wide to ignore. It’s possible that for-profits have cracked some code; maybe their clinical and administrative operations are more efficient without sacrificing the quality of care. At the same time, data suggests that gains in margins have come partly from leveraging weak spots in how hospice care is paid for. These tactics aren’t fraudulent, they’re just a product of incentives that arise from the hospice payment structure. More importantly, they raise the question of whether these practices harm patients currently in hospice or those who would benefit from it.

Hospice’s payment structure is unique

Hospices do a lot to care for our terminally-ill loved ones. A patient in their final days must be eased of pain, have their medications managed, their spiritual energy cultivated—the list goes on. It takes an interdisciplinary team to navigate this, with physicians, nurses, home health aids, social workers, spiritual guides, nutrition experts, and others. Each member plays their part to harmonize the person’s final days of life with comfort and some peace.

The way Medicare reimburses hospices is not your typical fee-for-service setup. Instead of charging for each procedure, hospices get paid a fixed daily rate. For every day they take care of a patient, they get a predetermined lump sum. Medicare’s daily rate is designed to cover all costs related to patient care—direct costs like labor, medical supplies and equipment, medications and even indirect ones like administrative and maintenance costs and employee benefits.

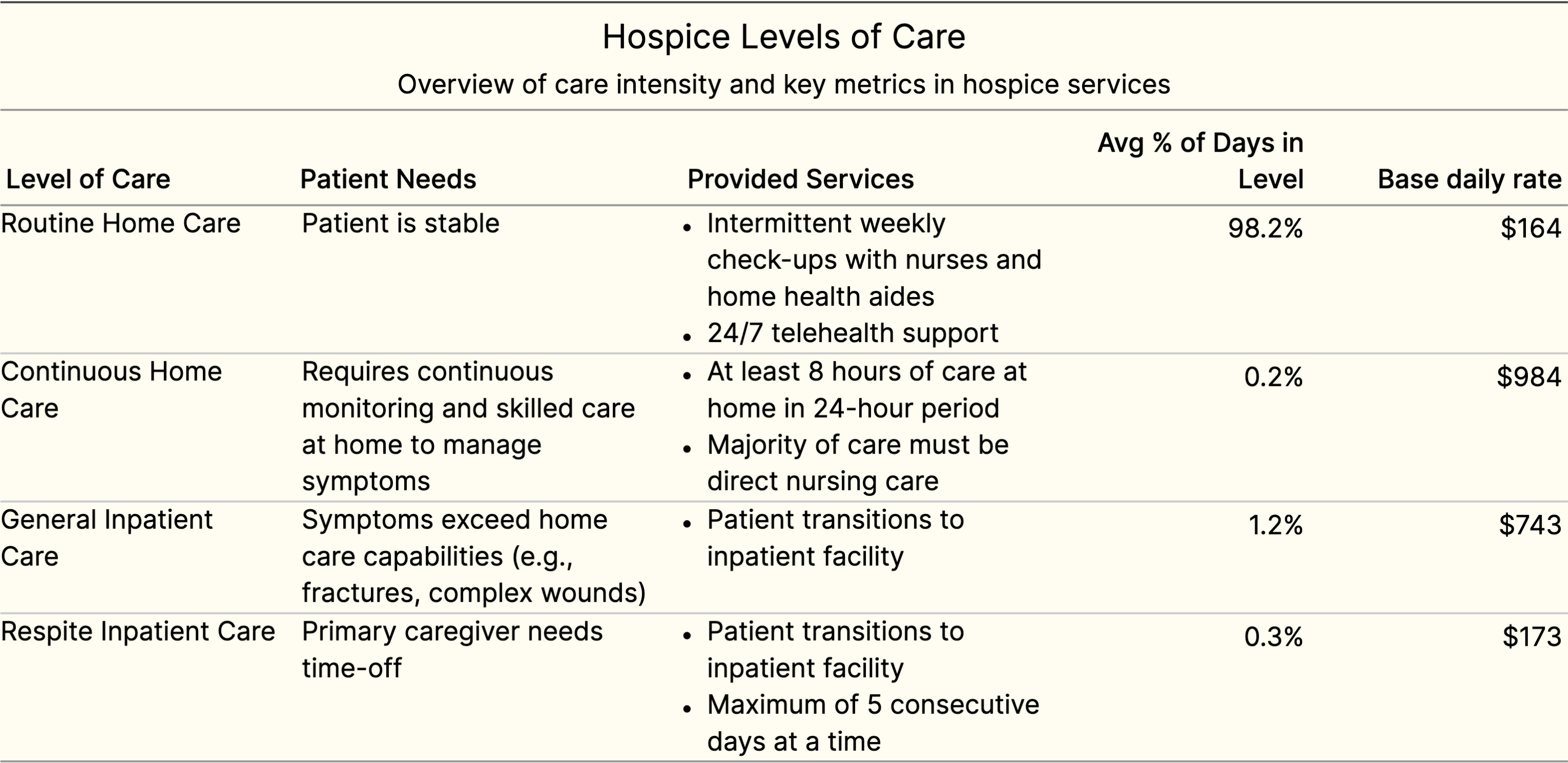

This lump sum depends on the “intensity of services” being delivered to the patient. And the patient’s condition and circumstances, which can change day-to-day, determine that intensity. If the patient is in critical condition and needs to be rushed to the hospital, the daily rate is higher. If they’re stable and just need intermittent check-ups, the daily rate is lower. Rates are pretty much the same for every hospice in the nation, but they vary slightly based on location to account for differences in cost of living.

Medicare has four different rates, one for each “intensity” or level of care.

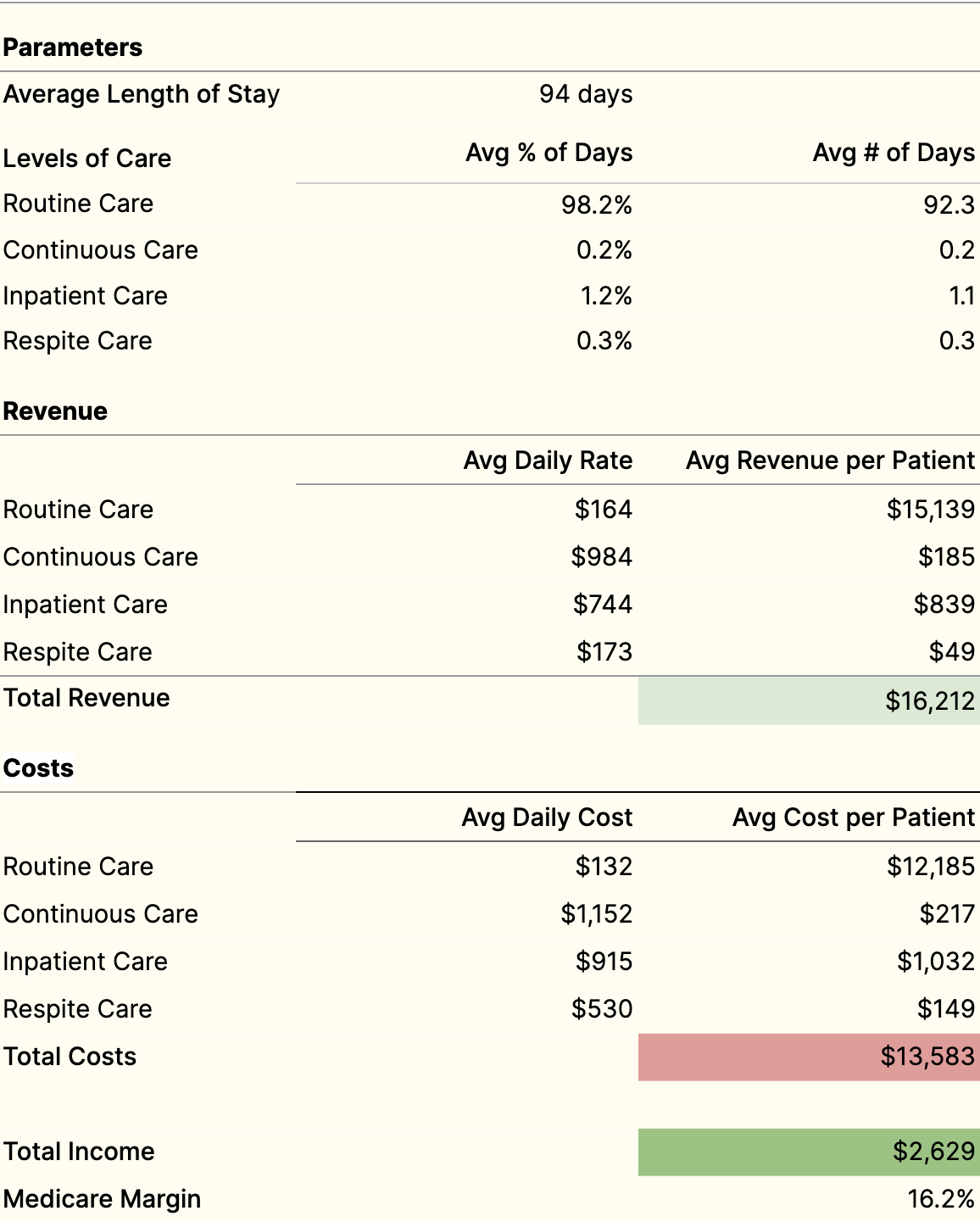

With some back of the napkin calculations, we can get close to the Medicare margin calculated by Medpac.

Quick note, Medicare margins are not your typical indicators of financial performance (like gross or operating margins). Medicare margins try to account for all the costs related to patient care, including some operating expenses like leasing equipment, paying for nurse administration, and subscribing to medical software. They also exclude certain direct costs for patient care that aren’t reimbursable like bereavement programs and salaries for physician fellowships. To estimate a typical profit margin, we’d have to dig up the publicly released hospice cost reports and recategorize costs ourselves.

Also, in our previous calculation, we only consider one patient. If we look at all patients, we can project gross revenue. Since hospices receive a daily rate per patient, growing revenue is straightforward: they need to admit more patients than they discharge or lose to death (current census = starting census + new admissions - discharges - deaths). So increase enrollments, or decrease discharges and deaths.

Trying to “decrease discharges and deaths” doesn’t make much sense. It’s not like hospices have control over how long their patients live. And yet, after Medpac examined hospice episodes across the nation, they found that hospices might be influencing how long their patients stay in hospice on average. And this is where it gets quirky.

Increasing average length of stay by selectively admitting patients

The data is telling: patients at for-profit hospices receive care for an average of 112 days, while those at nonprofits stay for only 72.

The large variance in length of stay is partly attributable to the types of terminal illnesses patients have. For-profit hospices have a different patient mix compared to nonprofits. For example, they tend to enroll more folks with neurological conditions, COPD, and heart failure than those with cancer. And it’s these noncancer patients who tend to live longer in hospice–nearly 100 days longer on average–than cancer patients. Indeed, not all terminal illnesses are equally aggressive.

You might think at this point: “Okay, more days means more revenue, but that doesn’t necessarily mean higher margins.” The surprising fact is that patients with longer stays also have lower average costs per day. The reason is because hospice care is particularly expensive at two key times: when a patient first gets admitted and in the last few weeks before they pass. The start of a stay requires an initial setup–clinicians create care plans, set up medications and equipment at home, educate caregivers, and complete administrative obligations. And during those final weeks, the patient might experience serious pain and discomfort and require high-touch care from skilled nurses.

But in between these two periods, patients, caregivers, and the care team are usually following a routine with intermittent visits every week. The relationship between length of stay and labor is a U-shaped curve. And the middle period is an incentive for hospices to want longer stays, to keep costs down across the entire episode.

And so the profit-driven hospice might say: “Sure, we could innovate our care model, reduce costs without cutting corners on care, but what if we just take people that are more likely to live longer in the first place?” There was a surprising study from Cornell that supports this. It looked at how the patient mix changed for hospices after they got acquired by private equity and corporate firms. Post-acquisition there was on average over a 10% increase in enrollees with dementia across these hospices.

Let me be clear. Longer stays in hospice aren’t necessarily a bad thing. In fact, people who could benefit from hospice often enroll far too late. Even though the average length of stay for the average patient is 92 days, the median is only 18. Yes, the majority of patients often miss out on what hospice care can really offer. There’s been a noticeable push for physicians to discuss hospice earlier with terminally-ill patients. The hope is to give people and their families more time to navigate their options and have an easier transition into hospice care.

But what is questionable is selectively enrolling patients who are likely to have longer stays in the first place. The correlations between profit, length of stay, and patient mix suggest that margin-motivated hospices might be doing this, but it’s ambiguous whether these patterns are due to deliberately manipulative practices or just unintended consequences of cost-saving strategies. There’s limited data on referral and enrollment tactics, and they reveal some insights, but no definitive conclusions.

Partnerships with assisted-living facilities are desirable

Hospice comes to you, wherever you call home–whether it’s your actual house or apartment, a skilled nursing facility, or an assisted living facility. Interestingly, Medpac’s analysis shows that for-profit hospices treat a far greater proportion of patients from assisted living facilities (ALFs). These hospices might prefer patients in ALFs because their disease profiles lend to longer lengths of stay. Folks in ALFs are more likely to have neurological conditions like dementia, and less likely to have cancer. A survey from Mount Sinai and Yale, also found that for-profits were less open to partnering with oncology-centers.

On the flip side, it could be the case that ALFs offer efficiencies that make them attractive. If the hospice is treating multiple patients living in the same place, it means lower transportation costs and less time wasted on travel for hospice workers. Plus, there’s a strong network effect when sourcing referrals from ALFs, and the ALF staff can help share the load of patient care with the hospice team.

Restrictive enrollment policies are barriers to complex need patients

Sometimes hospices have enrollment policies that require patients to give up certain treatments. This is in addition to the requirement imposed by Medicare’s hospice benefit, which says that if you want insurance coverage for hospice, you have to forgo curative treatments.

For example, one third of hospices deny patients who want to continue palliative chemotherapy and radiotherapy. These aren’t treatments meant to eradicate cancer. They’re palliative. They try to shrink the cancer, and in effect improve distressing symptoms.

You can’t blame these hospices entirely. Palliative cancer treatments can easily run over $10K. The root of the problem lies in the per-day payment structure. When a hospice takes on a patient needing expensive treatments, it can skew their average daily costs and narrow their margins to impractical levels.

There’s not a lot of accessible data on hospice enrollment policies. The studies are limited, and hospices are probably not eager to share this information. It’s hard to say exactly how much of an impact this has on access to care for patients with complex, high-need illnesses, and the extent to which high-performing hospices restrict enrollment.

Medicare caps a hospice’s total payments

Medicare has a clause in the payment structure that discourages hospices from enrolling patients too early or remain in care for too long. It’s a limit on the total amount of money a hospice can get paid. In 2023, the cap was about $32,000 per patient on average. So, if a hospice took care of 50 patients throughout the year, they’d have to pay Medicare back if they received more than $1.6M ($32K x 50) in reimbursements. That’s what’s called their cap liability.

Sometimes it seems like every rule meant to mold positive behavior introduces ways for it to be gamed. The cap liability is affected by two things: the number of patients a hospice serves in a given year and the average payments received per patient. Both can be fiddled with, especially in the months before the year ends, by changing how many patients a hospice enrolls or discharges. And again, if you take a look at the data, there’s some evidence that this is happening.

Cap liabilities can be decreased by tweaking enrollments and discharges

The cap liability is finalized after the year ends because it depends on the total number of patients the hospice took care of that year. Let’s keep going with the example from before. Say the hospice got $2M in payments that year. That means for each patient, they got an average of $40K ($1.8M / 50), and they’ll have to pay back $300K ($6K x 50). Not good.

The hospice realizes a few months before the year ends that they’re on track to go over their cap. What can they do about it?

Consider what happens if they enroll a patient who’s expected to have a low length of stay—maybe someone with end-stage cancer who unfortunately elected too late. Say this person ends up staying in hospice for 40 days, way less than the six month limit Medicare endorses. For this patient, the hospice will see about $12K in payments for their services. For simplicity, I’m assuming the average daily rate, across all levels of care, is $240, which comes from the fact that over 98% of a patient’s days are routine home care and $240 is slightly higher than the 2023 rates for routine home care. After these payments, the total payments for the year have increased by $9.6K, and the census has increased by 1. The total payment is now $1,809,600 and the average total payments per patient is about $35,600K ($1,809,600 / 51). See what’s happened? Their cap liability decreased.

Alternatively, another way to decrease liabilities is to discharge people who are expected to stay in hospice for much more time. A hospice can choose to discharge someone who has “gotten better” or whose disease trajectory is no longer aligned with Medicare’s six month eligibility criteria. The calculus in this scenario is simpler. If a hospice is on track to go over the cap or has already exceeded it, they won’t see any Medicare revenue for a portion of their services. For example, if a hospice has to repay $150K in liabilities and the average cost per day is $150, they will not receive payments for 1500 patient-days worth of service. So, if you discharge patients, you stop the bleeding on days of service which will incur costs but see no Medicare payments.

Designing incentives is difficult, especially in a system as large and complex as healthcare. The late Charlie Munger once said, “If you have a dumb incentive system, you get dumb outcomes.” I’m not in a position to judge whether the incentives in hospice are too simple compared to other industries and areas of policy. But I can say that the current payment structure is less than ideal and is likely pushing even the most well-meaning hospice operators to deliver subpar care. I’m looking forward to seeing how Medicare makes changes in the coming years.