EHR apps are not a garage project

Back in 2009, the Boston Children’s Hospital wrote a white paper for the New England Journal of Medicine titled “Ten Principles for Fostering Development of an ‘iPhonelike’ Platform for Healthcare Information Technology.” Their vision was to create a platform like the iPhone App Store but for EHRs. Over the next few years, this evolved into SMART-on-FHIR, a standard that allows health apps to securely connect, share and update data, much like how Mint securely links to your bank accounts and pulls your transactions, so it can organize your finances.

Fast forward to 2023, and EHR vendors must now implement SMART and FHIR APIs to stay compliant with federal health IT certifications. Major players like Epic, Cerner, Allscripts, and Athena have answered the call. In fact, they’ve had app galleries for some time now. Even more regulation has been passed to ensure these protocols are used: as of last year, hospitals in the CMS Promoting Interoperability program only get full incentive payments if their EHRs have these capabilities.

Fourteen years after Boston Children Hospital’s publication, let’s see how close we are to the app store that was envisioned. Perhaps it’s unrealistic to expect EHR app galleries to be as user-friendly and seamless as the iPhone’s. Fair. We can compare them to other enterprise tech sectors instead. Salesforce’s AppExchange has over 7000 apps and 12 million installs. SAP’s Store has over 2500 apps. Compared to Epic’s 640 apps, it might seem like healthcare is lagging. But it’s not a simple comparison. Not all enterprise use cases are equally complex. And healthcare apps have to run on different EHR systems, unlike apps for Salesforce or SAP, which cater to a single platform. Still, feedback from digital health companies suggests that developing apps has come with great friction.

In early 2022, the ONC surveyed key players in the interoperability market about their experiences with health app development and deployment. Their survey surfaced challenges with FHIR APIs, particularly those from EHRs. To put concrete examples to these challenges, we can look at a real-world case study from Yale New Haven Health System (YNHH) and their experience building a COVID-19 Tracker.

Prior to the COVID-19 Tracker, YNHH’s clinical workflow was a burden for both care coordinators and patients. Clinicians would refer COVID-19 patients to a care team, who then had to call each patient to get them set up. Patients would get a device to measure their vitals and had to regularly submit their data through a portal. Care coordinators then had to sift through these reports, calling patients who weren’t keeping up or whose health was getting worse.

The COVID-19 Tracker simplified the intake and review processes for care coordinators and made it easier for patients to submit their vitals and symptoms. YNHH faced some implementation challenges that align with the themes noted in the ONC survey. With this context, let’s dive into some of the problems that make app development for EHRs so tricky.

Developers rely heavily on proprietary APIs

FHIR is a work in progress, and EHRs are at different stages of implementing it. They’re incrementally exposing more FHIR resources and APIs, but in the meantime, developers often have to use vendor-specific APIs to fill in the gaps.

Apps focusing on patient data access have seen more success because regulations have pushed vendors to prioritize FHIR capabilities for this particular use case. But for other use cases like scheduling or payment processing, vendors have not yet implemented the necessary FHIR capabilities. This means developers have to rely on the vendor’s private API to get the job done. Using vendor-specific APIs makes it impossible for apps to work across different EHR systems. An app that relies heavily on Epic’s private API, for example, would need significant changes to work with a Cerner EHR. It also creates data silos, where information is stored in custom formats that require extra effort to convert into FHIR-compatible data for exchange or analytics.

Third-party integrators like Redox and HealthJump help by offering a single API interface to connect to various EHR systems. Life is made a little bit easier for developers. Connect to multiple health systems without getting tangled with EHR specifics.

Redox and HealthJump are API aggregators. The concept isn’t unique to healthcare. It’s similar to how Plaid connects with banks, Twilio with communication services, Stripe with payment systems, and Expo/Flutter with mobile app development.

Although not explicitly stated in their docs, it’s likely that Redox and HealthJump are using vendor-specific APIs behind the scenes. Of course, the catch with API aggregators is that your app’s reach is limited to the health systems in the aggregator’s network. To branch out, a new system would need to hop on board with the aggregator first.

In three cases, YNHH had to either use EHR’s private API or settle with a work around, even though FHIR had the features they needed.

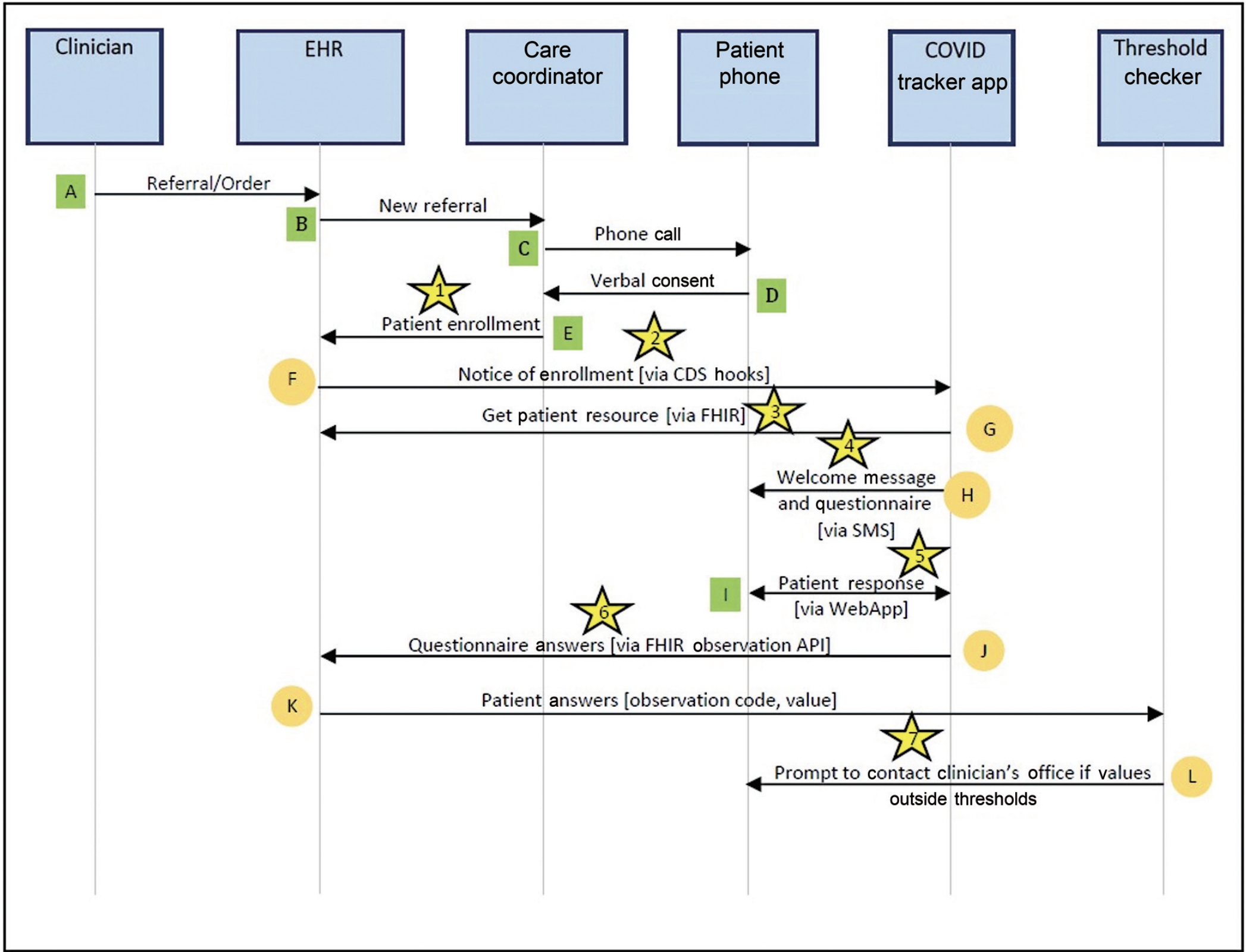

- Their EHR didn’t have the FHIR Subscription API. Because of this, their app couldn’t automatically notify care coordinators when a COVID-19 diagnosis was entered in the EHR. They used the EHR’s rule engine instead. Clinicians had to send a referral request to the care coordination team. This added an extra manual step to their final workflow.

- The EHR didn’t have the CommunicationRequest Resource, so the app couldn’t notify patients about enrollment through the patient portal. The developers had to send patients a text message instead. Patients had to use both their phone and the portal to communicate.

- Since CommunicationRequests weren’t available, care coordinators couldn’t get alerts about abnormal vitals and symptoms. The app had to encourage patients to contact their care coordinator.

Health systems have unique clinical workflows

EHRs are highly customizable. Providers will adapt the EHR around their unique clinical workflows. This flexibility is a positive. It allows providers to innovate and optimize their clinical processes. But it also presents challenges for app developers looking to automate workflows across health systems.

YNHH’s COVID-19 Tracker is a great example of an app closely tied to a specific workflow. The image below shows the app’s data flow with the steps involved for patient enrollment and monitoring.

But another health system might have some subtle differences that would impact the app’s design and implementation. I can think of a few:

- Different enrollment criteria: the health system may also want to include patients with chronic conditions or certain SDOH elements. The threshold checker may need to be modified based on the user’s health profile.

- Various roles responsible for monitoring patient-reported data: nurses or physicians may own this responsibility instead of care coordinators. As a result, the patient report may need to be surfaced in a completely different EHR interface.

- Diverse protocols for patient outreach: smaller care coordination teams may want to rely on more digitally oriented outreach by text or e-consent through a portal instead of phone calls.

So, how can you develop a plug-and-play app when workflows can be fundamentally different across clinics, especially if you don’t have prior information about the details of the workflow?

In the enterprise tech world, platforms like Retool help developers build custom apps quickly by offering no-code interfaces and a suite of connectors for connecting to endpoints inside and outside of an enterprise’s architecture. A similar tool tailored for healthcare IT apps, with connectors to FHIR APIs and helper functions for munging data, could be useful, with templates for common use cases. This would allow internal development teams at health systems to tweak apps to their specific workflows.

Security audits are not streamlined

We can expect that before a provider installs an app into their EHR, they will do a thorough security audit. Apps that extract data from the EHR and store it in some external system (call it a “data retention layer”) create liability for the provider. The more apps provider’s install, the higher the security risk. For apps that handle complex tasks, storing data is pretty much a must. This data work—things like removing duplicates, sorting, and combining data—will be critical, especially for analytics use cases.

As the app developer you certainly need to adhere to compliance standards like HIPAA, SOC 2, and ideally, obtain a HITRUST certification. But in my experience, these certifications don’t necessarily guarantee the trust of providers, and to be fair, that’s reasonable. As a result, you may need to complete security audits for every provider you integrate with. These reviews may vary from provider to provider, inspecting everything about your app infrastructure from encryption protocols, compute and database architecture, network configuration, and operational processes.

Products in cloud computing and developer tools present potential solutions. Backend-as-a-Service (BaaS) platforms, like Firebase and Supabase, offer standardized cloud environments out-of-the-box with built-in security features and compliance certifications. The advantage is clear for both developers and providers. Since BaaS platforms abstract backend development, app developers can focus on design without dealing with devops. And since cloud environments will look the same, with limited variation from app to app, providers won’t need to conduct custom, ad-hoc security audits for every app they want to install.

We could dive deeper. There’s a whole array of challenges that apps face when they try to chat with a FHIR server, and it’s not all about EHRs. Many of these are more fundamental to the FHIR standard and other legacy data formats, and I’ll save these for another post. It’s important to note that using SMART-on-FHIR and FHIR APIs is a must for any app that wants to exchange data with a server holding FHIR data. This applies to all sorts of apps, not just those within an EHR. Take CMS’s Blue Button API and Flexpa, for example – they live outside the EHR but still use these technologies. But for apps that live inside the EHR, FHIR APIs are just one piece of the puzzle.

Brendan Keeler recently tweeted about some of the inherent problems FHIR APIs face. And if you want to go down the rabbit hole, Alastair Allen and Thomas Beale have written about the leaky abstraction problem of FHIR.

I’ll close with a quote from one of the participants in the ONC survey.

We’re a lot closer than we used to be but I don’t think we’re at the stage where somebody can come up with an innovative app in their garage and actually deploy it to the healthcare system.