AI explainability in clinical settings needs work

We all know the blurb when it comes to explaining machine learning models in healthcare. Clinicians need to understand the reasons behind predictions when these models are used in care delivery. This need has been top-of-mind since the first days of ML in clinical settings, since atleast 1991, when William Baxt used a neural network to predict myocardial infarction in the emergency department. Now, just recently, the European Union passed a regulatory framework for AI systems, which requires providers to include explainability modules (and meticulous documentation) in offerings.

Despite all the progress in explainable AI, its current state is still lacking. Don’t take my word for it - the sentiment is shared by both ML researchers and clinicians using them in practice. For example, a system tested at UPMC for treatment recommendations found clinicians quick to dismiss predictions when they couldn’t reconcile the model’s explanation with their understanding of evidence-based practices. One clinician even said, “…she’s not hypotensive. So why in the world is the AI asking me to start pressors? I’m rapidly losing faith in Sepsis AI”. It wouldn’t be the first time.

Explainable AI in clinical settings has been underwhelming and potentially unreliable for atleast two reasons. First, current methods fall short in giving the kind of explanations that clinicians need. And second, explainability has been democratized into off-the-shelf open-source tools. Inner workings are now abstracted away, meaning AI product developers and clinical data scientists no longer need to deeply understand the intricacies of the methods (I’ll admit I’ve been guilty of this). As a result, developers and data scientists lack the mental models necessary to effectively communicate limitations to clinicians.

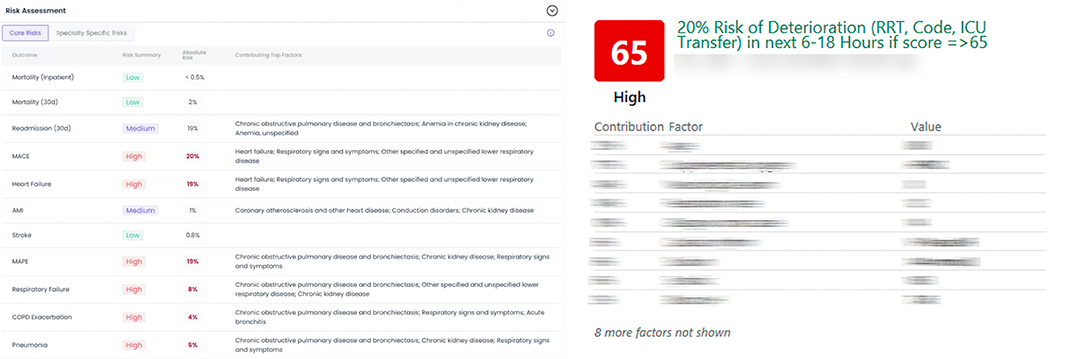

Interfaces showing predictions to end-users are pretty standardized. There’s an outcome, like an adverse event like hospitalization or onset of disease, and a patient score, which comes from the model. With with each score, there’s a list of “features” (also called variables, predictors, or factors) that were determined to be important to the model - the so-called “contributing factors” to the prediction.

To surface “contributing factors”, AI developers have rallied around one particular method called SHAP. SHAP is part of a larger family of techniques for determining “variable importance,” which itself falls under the broader category of model explainability. SHAP became mainstream around 2019 primarily because of its breakthroughs in speed and the high-quality software released by its creators.

DataRobot (a platform for building AI models for various use cases), describes SHAP’s role:

SHAP-based explanations help identify the impact on the decision for each factor.

The problems begin immediately. What does it mean for something to “impact” a black-box model?

What clinicians need from explanations

Before addressing that, we should probably know why we need explanations in the first place.

Imagine a clinician in the emergency department. They get an alert from a model indicating a patient is at immediate risk of cardiac arrest. They’re surprised, since they had just evaluated the patient minutes before, and they hadn’t suspect this. The clinician acts on the model’s alert - they administer vasopressors and fluids, even though the risk isn’t clear to them. When the patient later asks about this, the clinician will need to give an evidence-based explanation. Accountability is the first reason we need explanations. “The model alerted me” isn’t insufficient because models aren’t 100% accurate. Yes, they often outperform human judgment, but they’re not infallible. Understanding reasons behind a prediction helps identify when it might be wrong.

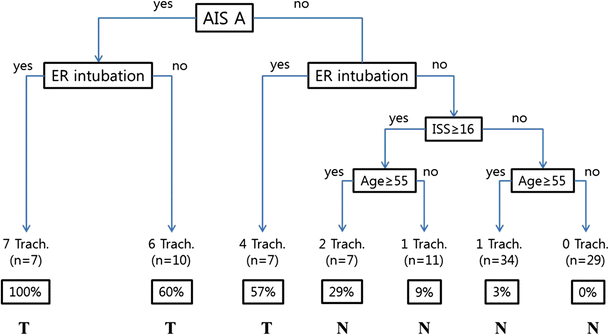

At a minimum, an explanation should include a statement explaining the model’s behavior for a prediction. For simple models, this is straightforward. For example, a simple tree like the one below can be easily followed.

ML models used in production are far more complex. Gradient boosted trees can have hundreds of trees, each much longer than the example. There is no single-paragraph summary to internalize this model’s behavior. There are far too many calculations done for a single patient for anyone to comprehend.

And so this is the grand endeavor of explainability. Can we summarize these thousands of calculations—perhaps discarding less important details—into a fairly accurate summary? We may not understand everything the model is doing, but if we can get a synopsis, we are in luck.

Particularily in clinical settings, there’s also a need to reconcile the model’s behavior with evidence-based practices. This might actually be more important than understanding the model’s behavior because clinical evidence enables clinical action.

There’s little consensus on the exact question that explainability should answer about model behavior. Some argue that only a causal account of why the model made a particular prediction—”Why did the model predict outcome Y instead of alternative Z for this patient?”—is satisfactory. This opens a can-of-worms about what makes a good explanation, which I’ll leave to the logicians and philosophers. We might find that SHAP is inconsistent at describing even simple model behavior for an outcome, let alone distinguishing between different outcomes.

What clinicians are actually getting

Let’s investigate what DataRobot says about converting SHAP values to statements about model behavior.

The [SHAP] contribution describes how much each listed feature is responsible for pushing the target away from the average.

…

They answer why a model made a certain prediction—What drives a customer’s decision to buy—age? gender? buying habits?

So higher SHAP values correspond to features that drive the prediction higher. Lower SHAP values correspond to features that drive it lower. It seems like we should be able to tell our clinician: “The model predicted outcome X because of features A, B, and C.”

This seems useful. Except that recent research questions whether it’s actually accurate. When we test the model, its behavior doesn’t seem to align with how SHAP says it should. There’s several known cases where SHAP fails to capture basic model behavior.

- SHAP values can show features as important even if the model doesn’t use them directly. This happens when unused features correlate with highly-predictive used ones. Example: a UW study trained a model to predict mortality using CDC data, where the final model didn’t use BMI. SHAP still assigned BMI a non-zero, positive importance. This happens because SHAP distributes importance between correlated features.

- Because SHAP splits importance between correlated features, key features the model relies on might appear less important

- SHAP values don’t indicate how a model’s predictions will change if feature values are adjusted. Example: a Stanford study used ML to predict survival outcomes in a clinical trial based on patient eligibility criteria. The author’s concluded that “Shapley values close to zero […] correspond to eligibility criteria that had no effect on […] the overall survival.” In other words, they expected that changing these criteria wouldn’t affect the prediction. You can test this: change the eligibility criteria and we should expect the survival score to change. Recent research from the University of Toronto found that this expectation is completely unjustified. SHAP values don’t reliably tell you how changes in features will affect the model’s output. The key insight here is that, with SHAP, we have no causal understanding of model behavior. The claim that the “model predicted X because this patient has characteristic Y” is invalid because it implies “if we change characteristic Y, the model should no longer predict X”.

Now what? Is SHAP just a crap approach to explainability? Or are DataRobot’s documents incorrect? We should revisit a fundamental perspective on explainability that is often overlooked in the race to build production-ready products.

How accurate can we really expect explainability to be?

SHAP and similar explainability methods are post-hoc rationales for black-box model predictions. These rationales are based on approximations of the model.

Since these explanations are approximations, they will be incorrect at times and can’t perfectly replicate the model’s behavior for all patients. If they could, we would never need the original model. Calling them “explanations” might be misleading; a more accurate term could be “summary of prediction trends.”

How exactly is SHAP an approximation of the original model? Let’s take a quick technical foray to understand how SHAP values are calculated. If a certain feature is important for a prediction, the prediction should change significantly if that model never had access to that feature. But it’s infeasible to determine this change definitively without retraining the model multiple times. We would need to remove each feature one by one and retrain the model at least once for every feature used in the original model. Instead, we can approximate the change. Approximating the prediction when features are “unknown” is the key innovation of SHAP.

The downsides of democratizing explainability

As I mentioned before, the creators of SHAP released excellent software. Anyone can use it without needing to understand underlying details. This is dangerous (through no fault of the creators). SHAP is not a simple algorithm. It’s based on principles of game theory developed by Nobel Prize winner Lloyd Shapley. On top of that, there are several nuanced algorithmic choices with significant implications. Despite SHAP’s mainstream adoption, it’s often assumed to be a complete solution when, in reality, it’s still a work in progress. Again, I’ll admit my own guilt here. There’s concern that these methods can only be used correctly by experts. The average users can easily fall into confirmation bias and develop incomplete mental models, leading to overtrusting the tool.

Another example. In 2015, Mount Sinai used an ML model to triage pneumonia patients. The model had excellent accuracy, but they eventually noticed something peculiar - it assigned a low probability of mortality to patients with asthma, which contradicted clinical intuition. Had they used SHAP values, they would’ve found that the presence of asthma drives the prediction score down, and clinicians might have said something like: “The model predicts a low mortality score for this patient because they have asthma.” They later discovered that historically, asthmatics with pneumonia were sent to the ICU due to their high risk, where the extra attention they received reduced their overall probability of death.

The root cause of Mount Sinai’s problem is a case of incomplete data, not the limitations of ML or explainability methods. But the case is an example of how someone may deal with counterintuitive interpretations. Confusing results are sometimes dismissed, especially in clinical environments where models are expected to provide new insights into disease management or physiology. People tend to rationalize that machine learning models process data differently from humans and rely on “a lot of complex math” to uncover things we might not fully understand. For Mount Sinai, this could have been dangerous.

Good data science teams vet their models with the clinical team. Still, I don’t see how all failure cases can be found before deployment.

Some researchers have called for abandoning black-box models in favor of simpler, naturally interpretable models. Others suggest using multiple explainability methods together, leveraging their strengths and weaknesses, in a way that allows the end-user to interact with an end-system. That’s a compelling idea, but it wouldn’t be feasible in a clinical envrionment - no clinician can spend 15 minutes reviewing explainability. Maybe as LLM agents become more robust, we could see a system where an agent, similar to how they are used to write code and build apps with human assistance, can use multiple explainability methods through an interactive interface to provide an accurate understanding of model behavior.

For now, we must ask: can we live without explainability? Do predictive models lose all value if we can’t trust their explanations?

A different approach: using AI to structure workflows

Whatever qualms you may have about explainability, there is no denying that ML offers benefits in accuracy compared to clinicians when it comes to predicting outcomes.

How can we leverage this benefit without depending on explainability? Lessons learned from a deployment done by Stanford offers a new perspective.

In 2022, Stanford deployed AI systems at Stanford Health used for surfacing seriously ill hospitalized patients who may benefit from advanced care planning (ACP). ACP helps clinicians identify patients who might benefit from palliative or hospice care. From their previous experience with clinical AI systems and feedback from clinicians, the authors knew the concerns clinicians have about AI, like how clinicians often disagree with ML predictions or feel the AI doesn’t provide new insights.

Stanford, in this deployment, emphasized AI’s utility in structuring collaborative workflows, rather than being correct or offering new insights. The AI model acts as a “mediator”, helping clinicians and nurses adopt a shared mental model of risk. The AI serves as an objective, initial assessor of risk. The motivation for this was an issue that they surfaced from stakeholder interviews - clinicians often noted that, in multidisciplinary teams, there is hesitation to take action due to disagreements between physicians and nurses assessment of a patients risk, which can lead to missed ACP opportunities.

Again, the AI’s role here is not about delivering detailed insights or ensuring agreement on individual predictions. In fact, the alerts generated by Stanford’s model do not even mention contributing factors. The AI model is just the first step in assessing risk. The alert triggers an assessment protocol—a “serious illness conversation guide”—where a nurse assesses the patient’s needs and goals, deciding on additional care management initiatives.

The approach still allows better allocation of resources by directing nurses to patients who would benefit most from ACP, addressing the issue of limited nursing resources and avoiding unnecessary ACP for patients who do not need it.